This site is a companion to:

This North Coast Place.

The following article appeared on the front of the

San Francisco Chronicle Datebook section on Saturday February 28, 2004, the day of the annual vigil marking the massacre of the Wiyot in 1860. I tried for years to get some publication interested in this story. It finally happened in early 2004. Though I didn't know it at the time, negotiations were already underway for the return of some 40 acres to the Wiyot, owned by the City of Eureka. I was later told that the appearance of this story was one factor that helped move these talks to fruition. This article gives more of the history than the above account of the signing celebration, both of the 1860 massacre and the more recent responses.

The Wiyot were not the only Native peoples subjected to violence by non-Natives in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some tribes suffered but survived with more population and land base; some tribes did not survive at all as ongoing cultures. Similarly, the Native peoples were not the only victims of violence and discrimination as a people, or an ethnic group. Humboldt County's treatment of the Chinese is nearly as notorious, and even some European groups, such as Italians, were at some time in some way not treated as full citizens. So we may want to think about these relationships, and the impact of this history on community today.

I've kept the structure of the Chronicle article's edited version, with a few clarifications and additions. The 2004 vigil, which I think was the fourth I'd attended, seemed larger than the year before. I'd guess there were 400 people there, including Paul Gallegos, Humboldt County's District Attorney. It was a dry but not entirely clear night. The event is held whether it’s raining (as it often does) or not, though in 2000 it was so stormy the event had to be moved indoors. That 2000 event is notable for several reasons: it was filmed for the Living Biographies project so a professionally shot tape exists as an archive; Cheryl Seidner announced that the first 1.5 acres of Indian Island had been purchased by the Table Bluff Wiyot Tribe, the culmination of a grassroots fundraising effort that captured the imagination of the community and beyond. And during the course of the vigil, Cheryl sang her "Coming Home Song" for the first time in public. That song has become a cherished part of these and related events ever since. More people heard that song on PBS than likely ever heard a Wiyot song, and probably more North Coast people, Native and Non-Native, have sung it together than any other Native song.

Like 2003, several dark necklaces of honking geese flew over during the course of the evening in 2004. Brian Tripp, a Karuk artist and writer, recited his powerful poem about the massacre, which I heard Julian Lang recite the year before last. The vigil ended with Cheryl Seidner singing her "coming home" song, with a "backup group" of Wiyot children joining in, and then everyone. It was dark by then, and I looked up to see a ring around the moon.

RETURN TO TULUWAT

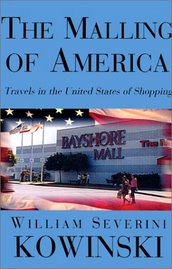

By William S. Kowinski

Special to the Chronicle

Just before dusk on the last Saturday in February, several hundred people gather each year at the edge of Humboldt Bay in Eureka, across from a small, tear-shaped island half a mile away.

Standing under a deepening blue sky flared with reds at the horizon (as they did last year) or under umbrellas in a North Coast late winter rain (as they did the year before), they will hold candles and share songs and prayers.

The forested land they can see across the bay, still called Indian Island, was the scene of one of the most notorious massacres in California history. At least 60 and perhaps more than 200 women, children and elders of the Wiyot tribe were slaughtered with axes and knives by six white men, known to be landowners and businessmen. This was one of three simultaneous attacks at different locations that sent this small tribe spiraling towards extinction, some 144 years ago.

For a long time, it seemed they were extinct. . As late as 1996, correspondent Fergus Bordewich wrote, "Little is known about the Wiyots." But the Wiyot tribe, denied federal recognition in 1953, regained it in 1990, and moved to a new reservation at Table Bluff, south of Eureka's city center, where some 450 tribal members now live.

"We are still here," said Cheryl Seidner, the elected Wiyot tribal chair since 1996, and a direct descendant of an infant survivor of the Indian Island massacre. "We are still a people. We still cast a shadow, we are not gone."

History Is

By a quirk of the California coastline, Eureka is the westernmost city in the 48 contiguous United States. Through the fate of history, it was one of the last places in America where Indians and Euro-Americans confronted each other. In a sense, it recapitulated and condensed several hundred years of American history in a few decades.

In 1860, California had been a state for only a decade, and the city of Eureka, growing from its docks to push against the redwood forests around it, had been the seat of the newly formed Humboldt County for just four years. The Humboldt Bay communities of Eureka and Arcata began by supplying the gold miners prowling the northeastern mountains, but by 1860 had opened nine timber mills, and were busily engaged in agriculture and ship-building. In 1853 alone, 143 ships left the bay loaded with timber, bound for San Francisco and other ports.

But far northern California had many small tribal groups of Indians living in its forests and mountains, and along its rivers and coast, some for 10,000 years.

The village of Tuluwat on Indian Island was the physical and spiritual center of the Wiyot world, which was comprised of some 20 villages spread over forty square miles, with a population of perhaps 3,000. There is evidence of Wiyot presence on the island for at least 1,000 years. But for many white settlers, Indians were a not-quite-human barrier to progress. Local newspapers supported a policy of extermination.

On the last Saturday in February 1860, the Wiyot completed their week-long world renewal ceremony at Tuluwat, to bring the world back into balance and mark the equivalent of their new year. The small boat arrived late that night, while the Wiyot men were away gathering supplies.

The massacre on Indian Island was not the first in the region, nor would it be the last. It was part of an accelerated pattern of destruction, beginning with random killings and rapes by miners and ranchers, and including kidnapping and legal slavery of mostly women and children under California's 1850 Indian indenture law. Later, Indians were forced into forts and small reservations under concentration camp conditions, and finally, those still living on their lands were subject to organized warfare by local militia while federal troops fought the Civil War. Together with the ravages of disease, this history reduced an estimated 15 local tribes to five.

But Indian Island became the most infamous massacre in northern California probably because of the presence of Bret Harte, who before achieving literary fame, reported for a newspaper in Arcata. His account of the massacre and editorial condemning its cruelty made him a local outcast, but anonymous letters to a San Francisco newspaper rumored to be his work were largely responsible for the national knowledge of this event. Editorial writers in San Francisco and in New York began referring to Eureka as Murderville.

Though the names of those responsible for the Indian Island massacre were apparently widely known, no legal action was ever taken against them. As Eureka became a prosperous commercial center, and Humboldt Bay became the busiest port between Seattle and San Francisco, this part of the past seemed better left forgotten.

But unlike much of California, the Indian populations indigenous to the Humboldt County area remained significant. Besides residents on Yurok, Hupa, Karuk and Wiyot lands and several Rancherias of mixed tribal groups, many enrolled members of indigenous tribes live and work in Humboldt's cities and towns. Though less than 6% of Humboldt's population, Native Americans are its largest minority group. In this large but mostly rural county(some 80% of it forested or devoted to federal and state parks), a bare majority of its population lives in communities surrounding Humboldt Bay, on land that once belonged to the Wiyot.

"The past is not dead," as William Faulkner wrote. "It's not even past."

The Wounds of Murderville

Seidner and her sister, Leona Wilkinson, began the vigils in 1992, together with two non-Indians, Peggy Betsels. former pastor of Eureka's United Church of Christ, and Marylee Rohde, former president of the Humboldt County Historical Society.

I've known about the story of the massacre since I was a little girl," Rohde said, "so I hadn't realized how deeply it was buried in Eureka's psyche. Peggy didn't hear of it until her daughter was in school, from the Native American parent of another student. But in talking with Cheryl and Leona, we realized that the story needs to be told. There needs to be healing, but the wound tends to fester if it's been suppressed."

"It's a healing of two communities," said Seidner. "It's not just us or them. We need to come together as a community of learning, to understand each other. That rip in our society needs to be mending, and hopefully we've been trying to do that for the last 13 years."

Community awareness of the Wiyot story increased dramatically in the late 1990s when Seidner began to raise funds for the purchase of the 1.5 acres of Indian Island where the ceremonies had traditionally taken place. At the vigil in 2000, Seidner announced that as a result of many small contributions from the local community, together with donations from Indian organizations and individuals nationally, the tribe had reacquired this land. The Wiyot would return to Tuluwat.

More funds are needed to clear the site of debris left behind by an abandoned shipyard, to erect the new ceremonial building, and perhaps acquire more of Indian Island. The Wiyot Sacred Sites Fund continues to raise money, partly through events such as the third annual benefit concert earlier this month. One source of continuing support has come from the local churches that recognize a special responsibility.

An anonymous letter about the massacre thought to be from Bret Harte was sent in 1860 to the San Francisco Bulletin asserting: "The pulpit is silent, and the preachers say not a word." "They did nothing, they said nothing," said Clay Ford, current pastor of the Arcata First Baptist Church. "We realized that we needed to take responsibility before God and before the Wiyots, for what Christian people did not do, even if we weren't there." After making a formal proclamation of repentence, Ford handed Seidner the first of annual checks, on behalf of the Humboldt Evangelical Alliance.

Another group, the Humboldt Interfaith Council (affiliated with the United Religious Initiative based in the Bay Area) is dedicating its community fund-raising efforts this year to the Wiyot Sacred Sites fund, including the proceeds from its Interreligious Peace Festival, being held on the Humboldt State University campus today.

"We're very passionate about what the Wiyots are trying to do," said Ross Connors-Keith, director of the group. The theme is the sacred arts---"especially dance and music, said Ross Connors-Keith, the group's director, "in keeping with the Wiyots' world renewal ceremony, which involved dance and singing. We thought this would be a wonderful way of bringing the community together."

At the Interreligious Peace Festival on the last Saturday of February this year, the Council will also present the Wiyot with a quilt made of individually purchased and decorated blocks (with proceeds going to the Wiyot fund), assembled by two county quilting guilds. "We selected a fish motif," Connors-Keith said, "because the massacre destroyed the Wiyot culture, and this is a theme that relates to their traditional way of life."

There have been other signs of reconciliation in recent years, as when Cheryl Seidner, about to speak to the Arcata Planning Commission in a public hearing concerning a proposed new center for the United Indian Health Service, spontaneously decided to welcome everyone to Wiyot country. It is an American Indian tradition for the host tribe to give permission to others coming onto their land. "I don't know if anyone has ever welcomed you before, and I want to be the one to do that" she said, and now recalls, "the roar that went up in the building was monumental---I couldn't believe what I had heard...The whole community that was there, it just exploded."

But in other ways, progress has been slow. "It's been a disappointment to me that I haven't seen more of the white population of Eureka interested in the vigil," Marylee Rohde says. "I think the wound is finally being acknowledged, but...Peggy Betsel's theory, and she did her dissertation about this at the theological seminary in Berkeley, is that this community had so much difficulty pulling together partly because this wound wasn't acknowledged. That burying it continued to poison what tries to happen."

"But we have seen participation in the vigil increase over the years from the Wiyots and other Native Americans," Rohde adds. "When I look back at the Civil Rights movement, I think maybe the healing has to happen with the victims first, before the perpetrators can acknowledge their own wounds."

But Marylee Rohde believes there's still progress to be made. "It's been a disappointment to me that I haven't seen more of the white population of Eureka interested in the vigil," she says. "But we have seen participation in the vigil increase over the years from the Wiyots and other Native Americans. When I look back at the Civil Rights movement, I think maybe the healing has to happen with the victims first, before the perpetrators can acknowledge their own wounds."

Return to the Center of the World

"The Wiyot are a people who are beginning to learn about themselves again," Cheryl Seidner says. "Culture gives us our identity. We are not just a name. We have to learn to live our culture, and try to incorporate it in our daily life."

"Cheryl stepped in at a transition point," observed Julian Lang, a language scholar and cultural activist whose ancestry includes Karuk and Wiyot. "Before Cheryl, the effort was to regain the Wiyot identity at the political level, to gain recognition and stabilize. Cheryl was able to begin charting a path of development at the cultural level, to begin the cultural rejuvenation. She's looking forward, representing the idea that there is a traditional ceremonial life ahead for the Wiyot."

Cheryl Seidner has worked full time at Humboldt State University since 1979. She is currently an administrator for the Economic Opportunity Program(though Governor Schwarzenegger has recommended it be abandoned.) Her older sister, Leona Wilkinson, recently retired from the Upward Bound program at HSU. But some fifteen years ago, Cheryl persuaded Leona to begin traditional basket-weaving again, which she had learned as a girl from their grandmother. The beautifully designed and water-tight woven baskets, caps and other items have both practical and sacred purposes essential to Wiyot life. Now she teaches her niece and grand-niece, beginning with the proper gathering of materials.

Basketry was easy compared to reviving the Wiyot language. There are no fluent Wiyot speakers left- only some tapes made in the 1950s. Marnie Atkins, Wiyot Cultural Director, is hoping to attend the "Breath of Life" conference at UC Berkeley for the second time this June, where she will be paired with a linguist to investigate the archives.

Meanwhile, she will be working with these tapes to create usable lessons that can be disseminated on CDs and over the Internet. Her goal is to get the language "into our ears, and into our children's ears."

Julian Lang has also studied these tapes, and combined what he learned with some singing derived from the Karuk culture for some classes he held for interested Wiyot a few years ago. "There was instant acceptance of that, and an incredible aptitude," he says. "People learned very fast. Lynn [Reisling, his partner in the Institute for Native Knowledge] and I were amazed. Within a month it was like all the cultural knowledge had always been there. It was close to the surface of everybody's soul."

Because February 1860 on Indian Island was the last time the Wiyot performed their world renewal ceremony, Seidner acknowledges that they will look to other local tribes for help in reconstructing it. Several have similar ceremonies, and they have traditionally participated in each other's dances. The rest, she says, "will come from our dreams. It's in our DNA."

With what Wiyot words she learned, she created her "coming home" song, which she sang at the end of a PBS airing of a documentary on American Indian sacred sites produced by the San Francisco based Sacred Land Film Project.

Sharing among tribes has already begun at the vigils. At last year's event, as participants gathered around the bonfire in the cold, clear night, Julian Lang looked up and remarked, "in Wiyot the word for 'stars' means 'God's eyes.'" Then he sang a song from the Karuk's world renewal ceremony, the Jump Dance. Joseph Orozco, a member of the Hupa tribe who is the station manager of KIDE-FM, the first tribally owned and operated public radio station in California, sang a mourning song based on the White Deer Dance.

All of this is also preparation for the future, when the vigil will be over and there will be ceremony at the end of February again.

"Cheryl recognizes that land is at the heart of the ceremony," Lang says. "Ceremony needs a place, and there's no more significant place than Tuluwat on Indian Island."

Seidner talks with enthusiasm about members of other tribes "who say, we can't wait to be back on the Island with you...It's getting to the point that they can feel it coming. It's been a real blessing. We realize we are not standing by ourselves.''